4 Things Guitarists Can Learn

From Pianists

In order to continuously improve, guitarists should study all kinds of musicians. In particular, there’s a lot we can learn from pianists.

The good news is that there’s a mountain of literature on how to play the piano. Most of the advice piano-players give to each other applies equally well to guitarists, so we should be more than willing to poach on their territory.

In this post, I’m going to focus on the advice of one pianist in particular—Josef Hofmann. His book “Piano Playing,” is one of the best I’ve read on how to be a great musician, and I’d recommend it to any guitarist.

1) Separate the material from the spiritual

According to Hofmann, there are two dimensions to mastering one’s instrument: the material and the spiritual.

The material dimension

He defines the material dimension as “that part of it which aims to reproduce in tones what is plainly stated in the printed lines of the composition”

The material dimension pertains to playing technique. For guitarists, that means how well we can handle all the gymnastic demands of being a guitarist: chord changes, barring, hammer-ons, pull-offs, strumming, plucking, harmonics, arpeggios, scales, shifting, muting, dynamics, tone colors, and so forth.

Of course, not all techniques are common to all styles of guitar. For instance, an electric guitarist is more likely to use right-hand tapping than an acoustic rhythm guitarist. You’ll naturally make judgements about what techniques your style of guitar calls for most, and train those the hardest.

Hofmann considers technique a kind of musician’s currency:

To move comfortably with freedom in life requires money; freedom in art requires a sovereign mastery of technique. The pianist’s artistic bank-account upon which they can draw at any moment is their technique.

Clearly, we should aim to improve our technique until our “artistic bank account” contains all the capital we’ll ever need.

2) Value the Morning Hour

Hofmann believed that the morning was the best time to practice. He encouraged his students to wake up early, getting in about an hour of practice before

breakfast. As he wrote, “The mental freshness gained from sleep is a tremendous help.”

The many benefits of waking up early have been validated by modern science. That isn’t to say that certain people can’t be successful night owls, but I do think they’re the exception rather than the norm.

Part of the challenge of being productive in the evening has to do with cultural expectations: we tend to associate the late hours of the day with rest and relaxation. This means that people who work hard at night have to swim against the social current, skipping dinners, parties, sports games, and so forth.

Yet I know that not everyone has time in the morning to practice. Most people have to wake up early and scramble to get to school or work five days a week or more. Thus, squeezing in a guitar practice might feel impossible.

Fortunately, Hofmann is an advocate of short practice sessions. In fact, he warns his students never to practice for more than an hour at a time, while setting no limits on how short a session can be. I know from personal experience that a brief 5-15 minutes can be more than enough time to make some progress, so I’d highly recommend adding a short session to your morning routine if at all possible.

4) Maintain A Large Repertoire

Hofmann was famous for his large repertoire. From 1912-1923, he gave 21 consecutive concerts in St. Petersburg without repeating a single piece, playing 255 works from memory!

He never claimed to have superhuman retentive powers, but believed that memory could be developed through use much like a muscle.

When asked how he recommended maintaining a large repertory of music, Hofmann wrote that a student should play through (slowly and carefully) each piece they know a few times a week. He believed in playing one piece after another, rather than repeating the same piece over and over.

One benefit to memorizing and playing a lot of music is that each individual piece stays fresh. If you only play two pieces, they’re both likely to get stale. However, if you’re always cycling through five or more, they’re all going to feel somewhat interesting when you return to them.

If you’d like to expand your repertoire but have trouble learning new music, I highly encourage you to do more sight-reading. Good readers can cover an incredible amount of musical terrain. If you want to lean more about sight-

reading, be sure to check out this post.

Conclusion

As I hope I’ve demonstrated in this post, we guitarists have a lot to gain by studying other instruments in addition to guitar. Music is music, after all. This isn’t to say you need to learn piano as a guitarist! Just be willing to pull from a variety of sources, and you’ll be in good shape.

Are there any other kinds of musicians that have inspired your guitar playing? Feel free to let me know in the comments below!

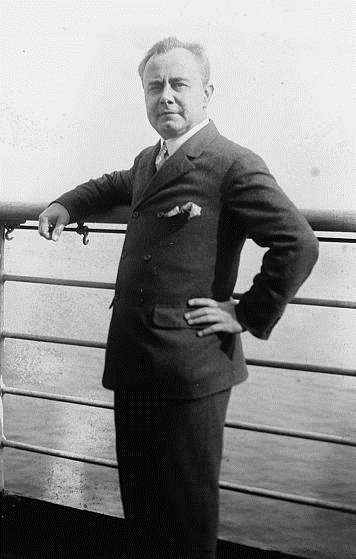

Who Was Josef Hofmann?

Josef Hofmann was born in Podgorze, Poland in 1876. He began playing piano at three and a half years of age, and was considered a child prodigy by the time he was six. At nine, he embarked on an international concert tour, stunning European audiences with his musical sensitivity and virtuosity.

A long and successful career followed this impressive start. Hofmann toured extensively throughout the world, eventually settling in California with his family. Aside from being one of the greatest 20th-century pianists, he was also a composer, music educator, and inventor, with over 70 patents to his name (including an early version of the windshield wiper).

Luckily for us, he began writing frequent articles for the Ladies’ Home Journal, which were later republished as his book, “Piano Playing.”

Without further ado, here are 4 pieces of advice from a great pianist of old!

The Spiritual Dimension

According to Hofmann, the spiritual dimension “draws upon and, indeed, depends upon imagination, refinement of sensibility, and spiritual vision, and endeavors to convey to an audience what the composer has, consciously or unconsciously, hidden between the lines.”

As you can see, this is the more nuanced, and probably more difficult, part of being a musician. Andres Segovia was speaking of the spiritual side of music when he used to tell students, “You must be more than perfect.” He expected his pupils to go beyond the written page, expressing the soul of a composition.

Spiritual excellence comes from many sources: theory knowledge, maturity, intellect, musicianship, feeling, spontaneity, etc.

So how do you improve this aspect of your guitar playing? I’ll list a few

suggestions below.

- Listen repeatedly to good recordings of the music you’re learning. The more interpretations you hear, the better.

- Study music theory so that you can understand your pieces from a composer’s perspective.

- Find a good teacher who can listen to you play and give you tips and ideas.

- Record yourself and listen to the playback, noting anything that doesn’t sound quite right.

- Attend as many musical performances as possible. Learn the history of the style of music you’re playing. Read biographies of musicians you admire.

- Train your ear to hear intervals, identify chords, and so forth.

These are just a few ideas, but I hope they give you a gist of what might help you “read between the lines” of the music you’re learning!

3) Think Carefully About Your Practice Strategy

Like many great musicians, Hofmann practiced in an intelligent and disciplined manner. He believed that fast progress came from quality practice. The question of how many hours a student should put in was always secondary; 1 hour of focused work can put 4 hours of distracted work to shame.

That said, Hofmann did give his students pretty specific practice advice. Ideally, they would practice for 2 hours in the morning and 1 hour in the evening.

He suggested the morning hours be used for technical work. The first hour should be dedicated to purely technical work such as scales, intervals, and arpeggios, while the second should be concerned with technical issues in a student’s repertoire.

After a morning of intense drilling, the evening hour be used for spiritual and interpretive work. A student should play through their pieces slowly, concentrating on proper dynamics, phrasing, rhythm, and the like. Any technical problems identified in the evening should be addressed the following morning session.

If you’d like more tips on how to practice, you’ll definitely appreciate this post!